What learning algorithms can predict that our physics theories might not

A hot topic in physics right now is applying techniques from information theory and theoretical machine learning to better understand physics. There are even hopes that these techniques might develop into a so-called “theory of everything” that unifies and explains all aspects of the universe. But for all the attention this subject has gotten, I’m a bit disappointed that I’ve never seen an introduction that explains

- where exactly might you be able to use learning algorithms where you can’t just use existing physics theories instead, and

- a hands on guide to applying learning algorithms in these situations, for people who don’t know information theory jargon

So I’m going to write one!

People often describe information physics or digital physics by saying it is something about the entropy of black holes, or the idea that we might be living in a computer simulation. While there’s a lot of important research along those lines, I think it’s even more important to understand why those ideas are worth studying in the first place. So instead, I’m going to start with the following idea:

If it is possible to put ourselves inside computer simulations, it might be possible to put ourselves in a situation where we cannot use existing physics theories to predict what we’ll perceive happening to us, but where we can use machine learning algorithms to do so.

But before we get into it, let me be very clear about something. Currently, information physics is just a hypothesis about how the universe works. Unlike more established theories such as the standard model and general relativity, we do not know if this is actually representative of how the universe works, or even if a new physics theory is needed to explain the situation hinted at above (where I emphasized “if” and “might”). Answering those questions would require serious experimental evidence that is way beyond our capabilities today. But given how quickly our technology is improving, I wouldn’t be completely shocked if it is possible in my lifetime.

Also, I should mention that I’m not one of the people doing research in this area, and despite my best efforts, it’s possible that I’m misunderstanding what these researchers are doing. So if you have any questions, comments, or corrections, please email me at firstestprinciple@gmail.com.

So first question: how might we be able to put ourselves in a computer simulation?

Putting ourselves in a computer simulation

If you haven’t been living under a rock, you’ve probably noticed that computers and software have gotten way better over the last several decades, and this trend shows no signs of stopping. So one study asked a bunch of AI experts when they think computers will become as smart as humans, and more than half predicted that this will happen before 2050.

If the optimists are right, we might see super-smart computers in my lifetime! But even if the pessimists are right, it’s fun to speculate about what really powerful computers would be capable of anyway.

Virtual reality simulations are already pretty good these days. If computers in 2050 might be smarter than humans, then virtual reality simulations in 2050 might be so good that to a simulated person living in one, it would look pretty convincingly like a real universe.

Instead of speculating about it, could we see for ourselves if that is the case? Perhaps it could be done like this. People have used brain-to-brain interfaces to think to each other over the internet, and the technology to do things like this is improving quickly. It wouldn’t be too much of a stretch to imagine that several decades from now, these brain-to-brain connections might have as much bandwidth as the neural fibers connecting the 2 halves of our brains. So if we hooked up two people’s brains together in year 2050, would they feel like a single person?

Better yet, what if we hooked up your brain to a simulated brain in a virtual reality world? Would you feel like you are also the person in the simulation?

We won’t know until we actually try it. If the answer is no then the rest of this blog post is completely irrelevant, but if the answer is yes then that would be really cool!

So let’s say you do that and you’re now a single person that lives in both the real world and a virtual reality world. Then the real world part of you gets into a tragic accident and your brain is blasted into a million pieces. How sad.

But are you really dead? Because, you know, people have done surgeries where they removed half of someone’s brain and they still lived on OK. So if half of your brain is in the real world and half of your brain is in a computer simulation and you lose the part of your brain in the real world, shouldn’t you still live on in the simulation?

If you try it out and the answer is no, then the rest of this blog post is completely irrelevant. But if the answer is yes, then it means that it’s possible to put ourselves completely inside a computer simulation! Isn’t that like the coolest thing ever? (If you like this sort of thing, here’s a Wait But Why post about what makes you you.)

So what does this have to do with information physics? Oh right:

If it is possible to put ourselves inside computer simulations, it might be possible to put ourselves in a situation where we cannot use existing physics theories to predict what we’ll perceive happening to us, but where we can use machine learning algorithms to do so.

So now I’ve explained the first part. But even if you can live completely inside a simulation (and this is already a huge if), the computers running the simulation must still follow the laws of physics. So if you know how the simulation is programmed to behave, you don’t need machine learning algorithms to predict what will happen to you. And if you gained enough knowledge about the state of the universe before your real world brain was blasted into a million pieces, then even if someone later decides to change the computer code of the simulation, then in theory you could predict that too. So what do you need learning algorithms for?

What our physics theories can’t predict

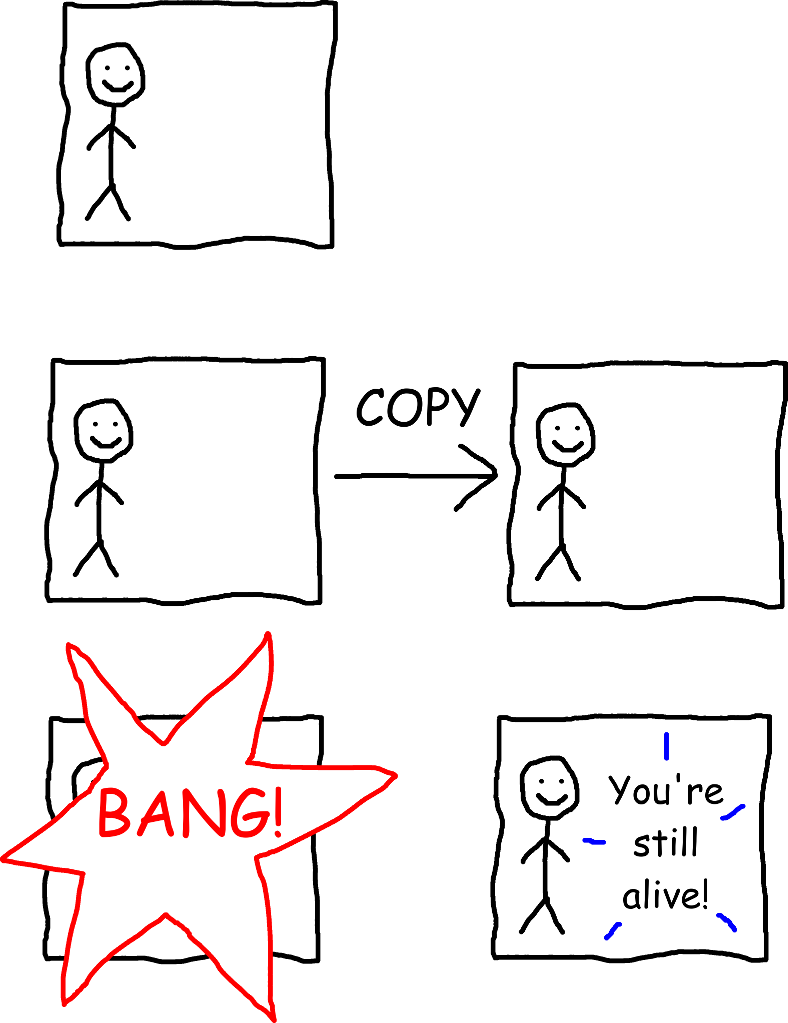

One really cool property of computer simulations is that you can make exact copies of them on different computers. If the simulation uses what’s called a “deterministic algorithm,” then it means that all copies of the simulation will output the same thing.

Now let’s suppose that after disconnecting your real world brain, the simulation you’re living in becomes deterministic, and that 30 seconds from now, it’s programmed to display a message to you saying “You’re still alive!” But those of us controlling the simulation are evil pranksters, and we decide to play a trick on you. Once the simulation becomes deterministic, we copy it onto a second computer, and right before it displays the “You’re still alive!” message, we blast the original computer into a million pieces. Now here’s the question: do you get to see the message?

Well, it depends on how we define “you,” doesn’t it? If we define “you” based on which physical body you’re in, or which physical computer you’re in, then you “die” in the original computer and don’t get to see the message. (Arguably, by that definition, you die even earlier, when your physical human brain is blasted into a million pieces.) But if we instead define “you” in a different way where it doesn’t matter which physical body or computer you’re in, then maybe you do get to see the message.

But here’s the thing. The way science works is that you’re supposed to do experiments to figure out what’s right and what’s wrong. And what we just described here is a way for you to experimentally determine which of these definitions of “you” are wrong! How? By attempting to put yourself in a computer simulation, then having some friends move the simulation to a different computer as described above. If you die before you see the “You’re still alive!” message, then definitions of “you” predicting that you see the message are wrong. If you do get to see the message, then you know for a fact that definitions of “you” predicting that you do not see the message are most definitely wrong! (One weird thing about this experiment is that people watching the computers from outside don’t find out which definitions of “you” are wrong, but they can still reproduce the outcome for themselves by putting themselves inside a simulation.) [1]

I’m going to use the terminology of the Wait But Why post I linked to earlier, and I’m going to call the hypothesis that you do not see the message the “brain theory.” And I’m going to call the hypothesis that you do (with greater than 0% probability) see the message the “data theory.”

As of today, we don’t know which hypothesis is right. But think about what it would mean if the data theory is right.

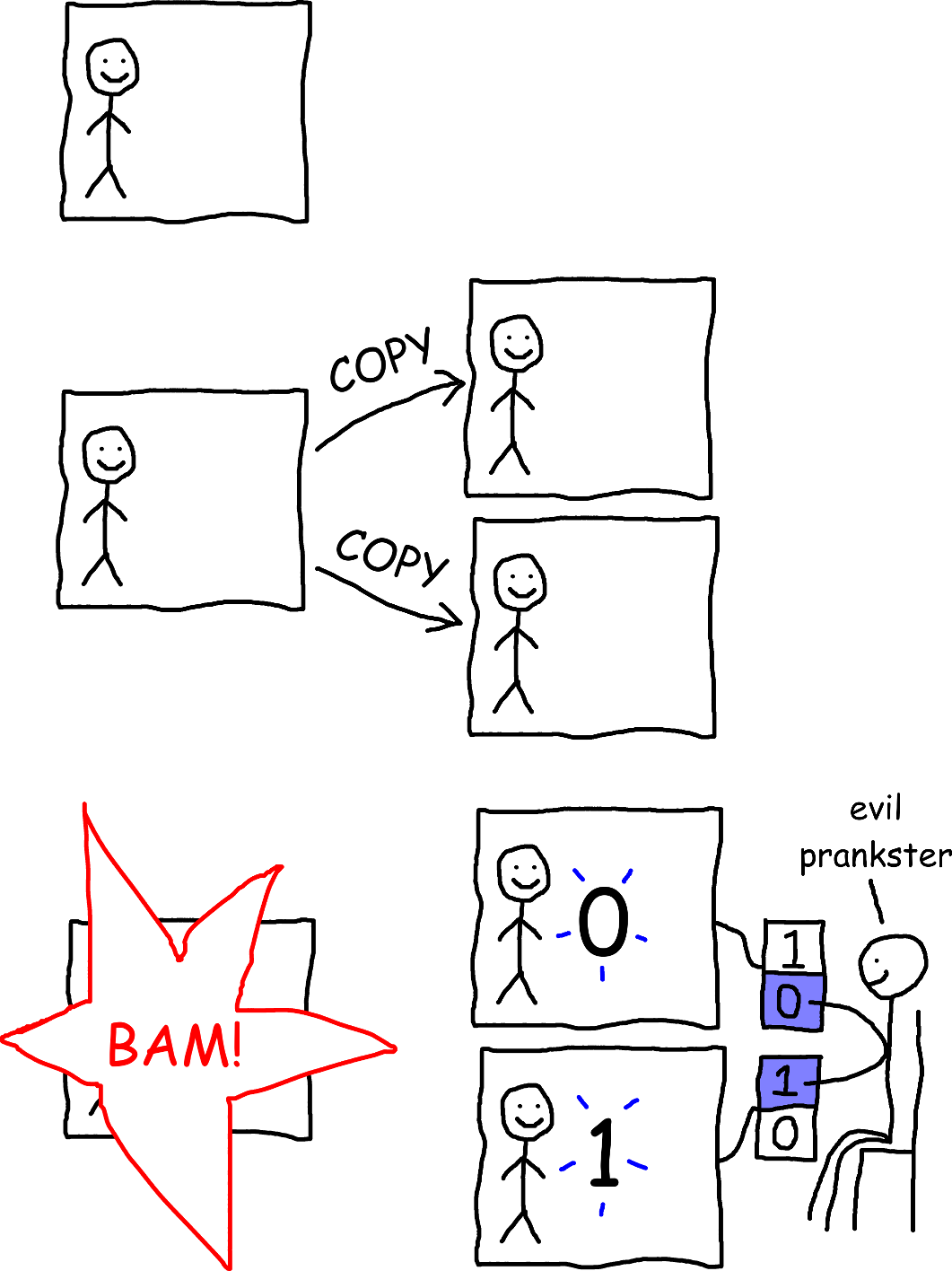

Well, that would mean we get to do an even crazier experiment! Suppose we do the same experiment as above, except for the following:

- The evil pranksters copy the simulation onto 2 other computers, instead of just 1.

- The simulation is deterministic, except for one thing: if someone presses a key on the keyboard, you get to see which key they pressed from inside the simulation.

- After the first computer is destroyed, someone presses the

0key on the second computer, and simultaneously presses the1key on the third computer.

Will you see a 0 or a 1?

Easy, right? Isn’t there just a 50% chance that you’ll see a 0 and a 50% chance that you’ll see a 1? Not so fast. Just because there’s 2 possibilities doesn’t necessarily mean that each one has a 50% chance of occurring. For example, if you consider the possibilities of whether or not you’ll be struck by lightning within the next 10 seconds, it is far more likely that you will not be struck by lightning.

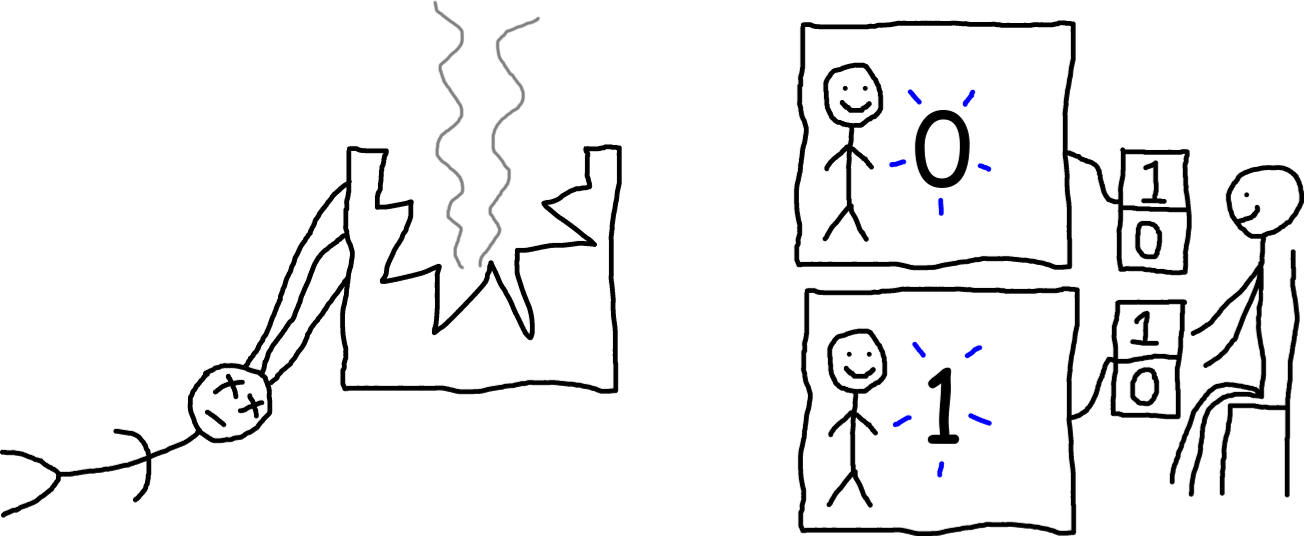

Well, then, how about we do this the proper way, and use the fundamental laws of physics to derive what’s going to happen? Well, the most fundamental physics theories we know of today are the standard model of particle physics and general relativity. And if you do the painstaking calculations, they’ll tell you that the outcome of this experiment looks something like this:

Here’s the thing. While these theories can give you a probability distribution over what every atom in those computers is going to do, neither of them say how to figure out who “you” are. So if you happen to know that “you” are a person being simulated in 2 computers (but you don’t know which computer you’re in because both copies of you have identical memories), and one version of “you” is going to see a 0 and the other version of “you” is going to see a 1, these theories cannot predict the probabilities of either version being the “real you!” [2]

Of course, if the brain theory is right and you die before you would see either the 0 or the 1, then this doesn’t matter. But if the data theory is right and there’s a nonzero chance that you do see either the 0 or the 1, then that would mean it’s possible to do an experiment in which the most fundamental physics theories we know of today cannot predict the probabilities of you seeing a 0 or a 1!

In that case, we’d need a new physics theory to fill the gap.

Have you tried…

(I added this section in Oct 2016 and have revised it since then)

To clarify, the standard model does predict probabilities of you observing a 0 or a 1 if you define the quantum state of the observer (i.e. “you”). But in order to do that accurately, you have to know precisely where you are in the universe, and the mainstream interpretations of quantum mechanics don’t say how to figure that out. Normally this isn’t a problem because as long as the quantum state of “you” is sufficiently correlated, or “entangled,” with your surrounding environment, you can get away with a rough approximation of the “observer” and still make extremely accurate predictions about what you’ll observe. But if you can ever put yourself in a simulation, using the standard model to predict which parts of the universe you’d observe would require an extremely precise understanding of what the quantum state of “you” actually is, and the obvious ways of defining it would not predict the correct probabilities of seeing a 0 or a 1 from your perspective inside the simulation described above. (This is just with “normal” non-quantum computers - uploading yourself into a quantum computer would raise its own set of questions.)

For example, if we define the initial quantum state of “you” as the quantum state of the particles in your brain, then thanks to decoherence, the standard model would predict that you would quickly become very entangled with both computers. In other words, quantum mechanics would predict that in a certain sense, you’d be able to observe both a 0 and a 1 (like people watching the computers from outside), not one or the other. This would be true for any reasonable-sounding definition of “you” based on the quantum states of physical particles.

If we instead define the quantum state of “you” as the quantum state being simulated in the computers, this would only make sense if the computers are actually simulating quantum mechanics. But even in that case, the no-cloning theorem and no-teleportation theorem imply that any quantum state stored as classical bits cannot be precisely the quantum state of “you.”

One possibility is that maybe you cannot be uploaded to a classical computer after all, but you can still be uploaded to a quantum computer, since unknown quantum information cannot be copied (though it can be moved). Even if that’s true, though, this explanation alone still doesn’t address the underlying problem that the standard model doesn’t define where you are in the universe. For example, if someone’s going to cut the bundle of nerves connecting the 2 halves of your brain, how would you use the standard model to come up with probabilities of finding yourself in the left or right hemispheres?

A few of my friends have suggested that perhaps this isn’t an experiment in the first place, but rather a metaphysical question without a universally correct answer. I can see both ways on this one, but keep in mind that whether you see a 0 or a 1 (or whether you see your left or right visual field after a split-brain surgery) is definitely something you can observe, and if you can observe it, you can disprove hypotheses about it using the scientific method. Even though other people won’t observe the result that you observe, they can still reproduce the experiment by performing it on themselves. So whether or not you consider questions about who you will be in the future to be a part of physics, you can still answer them for yourself using the scientific method, and we really ought to have a mathematical framework to help you do that.

If I missed something, please email me at firstestprinciple@gmail.com because I am extremely interested in this topic.

Enter the learning algorithms

Remember that at the beginning of this post, I promised to tell you about how people are “applying techniques from information theory and theoretical machine learning to better understand physics?” Well, now I get to tell you about that. But before we get into how you might figure out the probability of seeing a 0 or a 1 in the situation above, let’s start with a slightly different question.

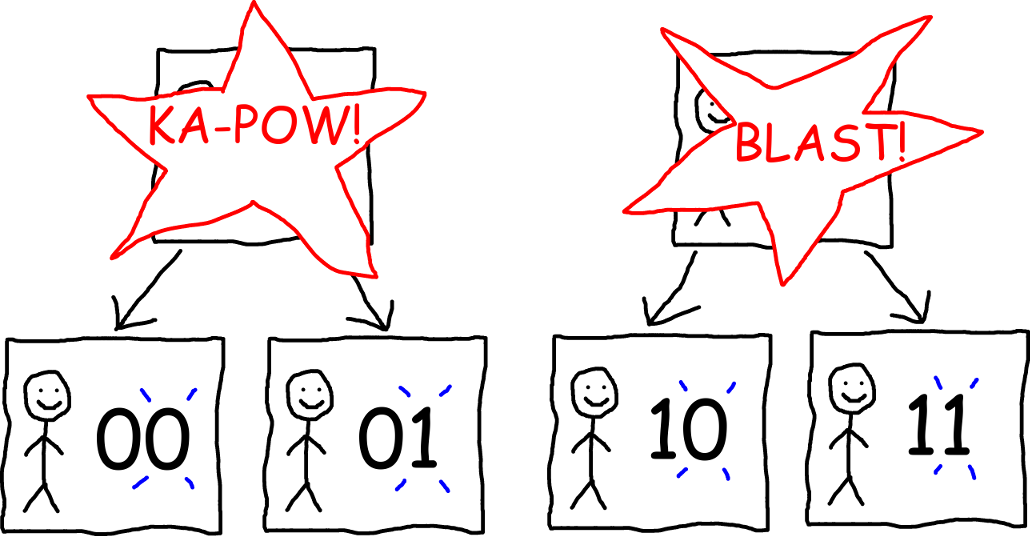

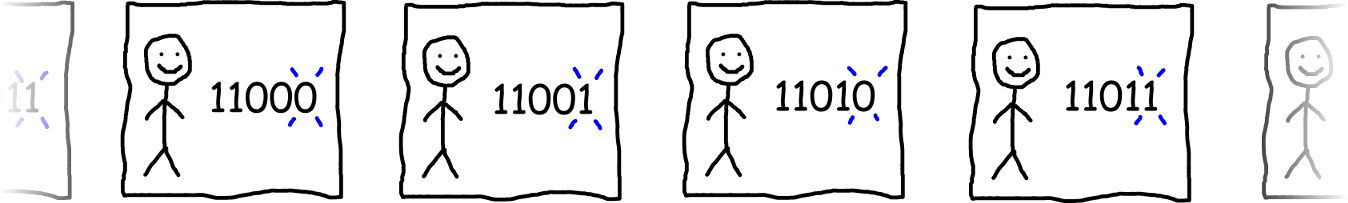

Suppose we do the experiment above, and you end up seeing either a 0 or a 1. (I’m going to assume from now on that the data theory is right, though this is still an open question.) But since those of us controlling the simulation are evil pranksters, we play the same trick again on both copies of “you” so that there are now 4 versions of “you:” a version that sees 00, a version that sees 01, a version that sees 10, and a version that sees 11.

Then we play the same trick again, so that there’s a version of “you” seeing each 3-digit sequence of 0’s and 1’s. Then we play the same trick again, and again, and so on, until we run out of money to buy more computers. (I imagine computers will be pretty cheap in year 2050.)

Now you can start to see a pattern. Inside the simulation, you see a sequence of 0’s and 1’s that keeps getting longer and longer. So considering the sequence that you’ve seen so far, how can you guess whether the next digit will be a 0 or a 1? Great question, and this sounds like a great time to talk about learning algorithms!

The most badass learning algorithm ever invented

Machine learning is a really big field, and there are way too many learning algorithms to cover them all here. Many of these algorithms exist either to address practical, real-life problems such as performance or perceived theoretical problems such as runtime complexity. But if you are a godlike being who is not concerned with either of these problems (and let’s face it, we all wish we were), there is really only one learning algorithm you need to know, and it is called Solomonoff induction. [3]

Here’s the problem that Solomonoff induction is designed to solve: suppose there is some unknown process generating a sequence of 0’s and 1’s (also known as a “bitstring”) and you want to guess the next digit (or “bit”) in the sequence. (Sounds familiar?)

So how might you do that? Intuitively you’d think that the next bit will probably continue the same pattern as the previous bits, rather than being something “random.” But how can you tell how “random” a bitstring is? A subjective but really effective way of doing that is by figuring out what are the lengths of the shortest computer programs that output that bitstring. So let’s use this idea to assign a probability to every bitstring.

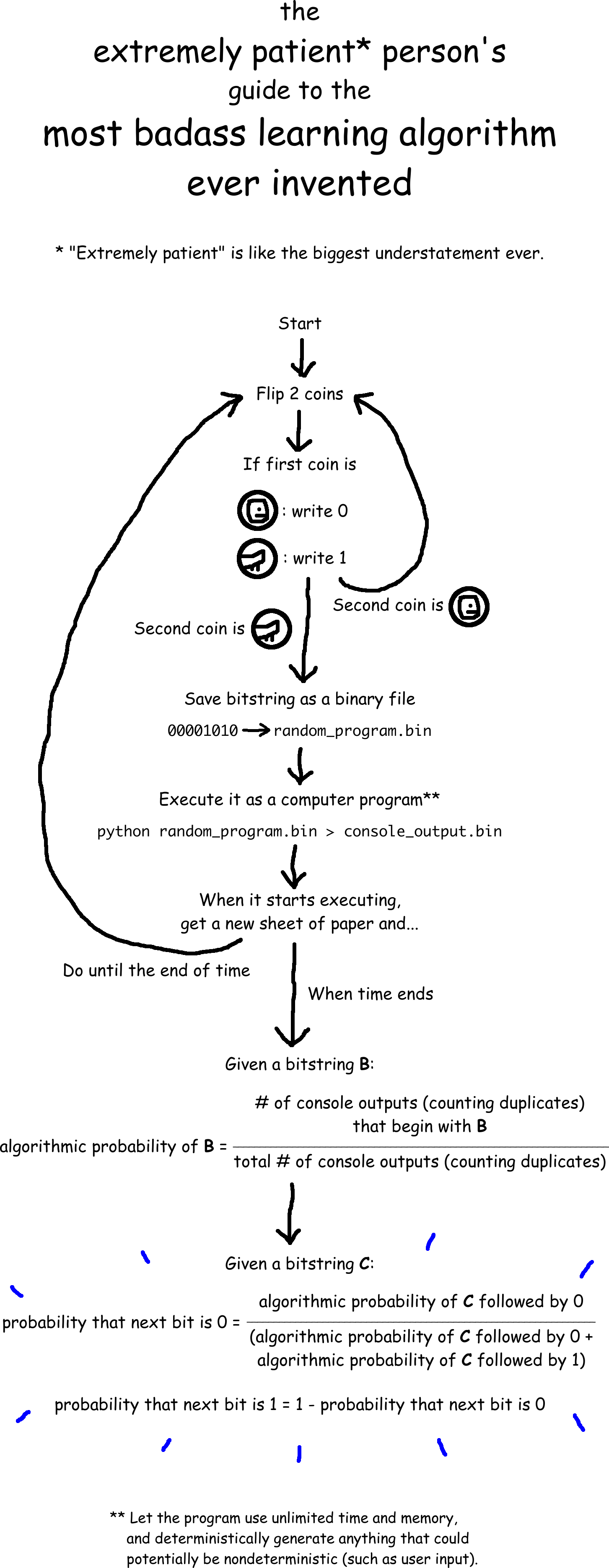

First we need a way to randomly generate computer programs that produces shorter programs more often than longer programs. Easy! Flip 2 coins. If the first coin lands heads then write a 0; otherwise write a 1. If the second coin lands heads then flip both coins again; otherwise stop. The resulting bitstring is our computer program. (We normally read computer code as text, but it is stored on computers as a bitstring.)

Next we need this computer program to output a bitstring. Simple! Save the computer program as a binary file and run it using your favorite programming language, perhaps Python or JavaScript. [4] Let the program use unlimited time and memory, and deterministically generate anything that could potentially be nondeterministic (such as user input). Of course, almost all randomly generated computer programs will have a syntax error, but that’s OK because there is still a chance that the program will run and print something to the console. Let’s call the text that the program prints to the console the console output. (This is also stored on computers as a bitstring.)

Now we can assign a probability to every bitstring you might see in the simulation. If you generate and run random computer programs, over and over again for the rest of your life and a long time beyond, we can define the algorithmic probability of a bitstring to be the number of console outputs (counting duplicates) that begin with the bitstring in question, divided by total number of console outputs (counting duplicates), as the number of console outputs approaches infinity. [5]

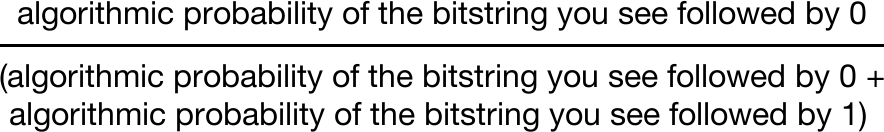

Finally, you can use these concepts to predict whether you’ll see a 0 or 1 next. According to Solomonoff induction (another source), the probability of seeing a 0 next is:

And the probability of seeing a 1 next is just one minus the probability of seeing a 0 next.

Phew, that was a mouthful! If you like, here’s a flowchart:

Why is Solomonoff induction badass?

That’s a crazy-looking algorithm, isn’t it? But you may still be wondering what’s so badass about it. Well, imagine a computer like the ones today, except that this computer has an infinite amount of disk space and access to a truly random number source (as opposed to an imperfect pseudorandom number generator). One of the deep results of information theory is that if the underlying process that “chooses” whether you see a 0 or 1 could in theory be simulated by such a computer, then as the sequence of 0’s and 1’s you observe gets longer and longer, the probabilities of future observations predicted by Solomonoff induction will converge towards the “fundamental” underlying probabilities.

Is it possible to define a process that Solomonoff induction cannot predict (in the sense of whether its predicted probabilities approach the true underlying probabilities)? The short answer is yes, but the kinds of computers needed to simulate these processes don’t exist in the real world, and it’s unlikely that we’ll ever be able to build them. This is why in my opinion, Solomonoff induction is the most badass learning algorithm ever invented.

Or is it?

One example of a process that Solomonoff induction cannot predict is one that loops over every possible program in your favorite Turing complete programming language, and for each program, displays 0 if it would run forever and displays 1 if it would halt. If we could ever simulate that process then it would completely upend our understanding of the universe. It would also scientifically demonstrate that Solomonoff induction is in fact not the most badass learning algorithm ever invented, because it would mean that we can predict processes that Solomonoff induction can’t by running an even more badass learning algorithm that is just like Solomonoff induction, except that you run the randomly-generated programs using a programming language that can solve the halting problem. What’s more, that link actually describes an infinite family of programming languages that we can use to define an infinite hierarchy of Solomonoff induction-like algorithms, where algorithms higher in the hierarchy can predict sequences that algorithms lower in the hierarchy cannot. Unfortunately, the kinds of computers needed to run these more-badass-than-Solomonoff-induction algorithms don’t exist in the real world, and it’s unlikely that we’ll ever be able to build them. [6]

Predicting the first digit, and other stuff too

Since Solomonoff induction is a learning algorithm, it only gives meaningful predictions after it has some measurements to learn from. So how could you approach the problem of predicting whether the very first digit you see in the simulation will be a 0 or a 1?

Thankfully, there’s still a lot of prior knowledge you can take advantage of. For example, one thing you could do (in theory at least, since it’s completely unrealistic to do this in practice) is take a video recording of everything you see, and use Solomonoff induction to predict how it will continue. Then you can fast-forward through the video streams it considers most likely to see if they show a 0 or 1 in them. Since videos are ultimately stored on your computer as bitstrings, it is still possible to run Solomonoff induction on them (though you’d want to use a different variation than the one I described in order to predict more than 1 bit at a time), and all of the same guarantees about its accuracy will still apply.

Heck, in theory this is something you can do to predict the future today, without waiting until we have the technology to potentially put you inside a simulation. This raises the question of whether Solomonoff induction might in fact be the “theory of everything,” or the ultimate physics theory that unifies and explains all aspects of the universe. Such a statement would imply deep things about the fundamental nature of the universe, and this is in fact an area of research, though as of today it is quite controversial. But it’s also possible to apply information theory concepts to study physics without necessarily assuming that Solomonoff induction is the theory of everything, and this is also a major area of research.

The technological singularity

Let’s get back to the big picture. Our technology has improved a lot in the last few decades. And not only has our technology improved, but the rate of improvement is accelerating. So what if this keeps happening? If we take this to the logical conclusion, doesn’t it mean that our technology would eventually improve so quickly that we’d rapidly evolve into a completely new, super-smart species?

People call this hypothetical event the technological singularity, and the only thing we know for sure about it is that we don’t have a BLEEPing clue what will happen when it occurs. I think these recent physics developments demonstrate the extent to which this is true. We don’t just not know what would happen socially, biologically, or technologically. We don’t even know what could happen on the level of fundamental physics!

Obviously, I think we need to do a lot more research to figure out what sorts of things will be possible when the technological singularity occurs, so we will be better prepared if it happens. But here’s what I hope will happen:

Remember the first stick figure drawing in this blog post, which speculated that if we connected 2 people’s brains as effectively as the neural fibers that connect the 2 halves of our brains, they might feel like a single person?

What if instead of connecting just 2 people’s brains together, we connected everyone’s brains like that to the internet? Would that mean that every human being on Earth would feel like they are just one small body part of a single, greater being?

We won’t know until we actually try it. But if the answer is yes, then it would mean that we’d finally be able to say “I am superhuman.”

Questions? Comments? Found a mistake? Email me at firstestprinciple@gmail.com.

- Could you instead define “you” as “anything that perfectly describes what will happen to you in the future,” so that whether you see the message doesn’t depend on the definition of you? You could, but the problem with this is that at a fundamental level, you don’t know exactly what will happen to you in the future. Defining “you” this way cannot help solve this underlying problem, but doing an experiment can. ↩

- You may be wondering why it matters which version is the “real you” if they are both “you.” But you have to keep in mind that if there are 2 versions of “you” where one version sees a 0 and the other version sees a 1, it would look very different when you are actually inside the simulation compared to if there is a single version of “you” that sees both a 0 and a 1. In the case that there are 2 distinct versions of you, there must exist probabilities of each version being the real you. ↩

- Technically speaking, Solomonoff induction is not an algorithm because it takes an infinite amount of time to return the final result. But I couldn’t think of a better word to describe it. ↩

- It doesn’t matter which language, as long as it’s Turing complete and has something like print or console.log that prints to the console. ↩

- I’m defining algorithmic probability somewhat differently than the link I gave, which defines it in terms of programming languages called universal Turing machines. But the key property is that you can use it to predict the output of any computer using the minimum amount of data, as I’ll explain later. ↩

- If those Wikipedia articles make your brain explode (don’t worry, they do that to me too), here’s a somewhat more accessible introduction to the problems harder than the halting problem. ↩